Surrounded by tall grasses, it’s easy to admire the beauty of this place. Countless bird species call to each other over the soft hum of crickets. Pollinators like monarchs and bumblebees abound amongst the wildflowers. I spot gnawed tree stumps courtesy of beavers along the rugged path as a goldfinch darts into view. Just as soon as the senses get a reprieve from city life, a screeching railroad car cuts through the peace followed by beeping trucks somewhere in the distance. Unfortunately, we are not here today to appreciate the wildlife but to assess the damage from a roughly 720-gallon diesel spill in Battle Creek by Canadian Pacific Railway, the effects of which have silenced frogs along the banks heard by park goers just the week before.

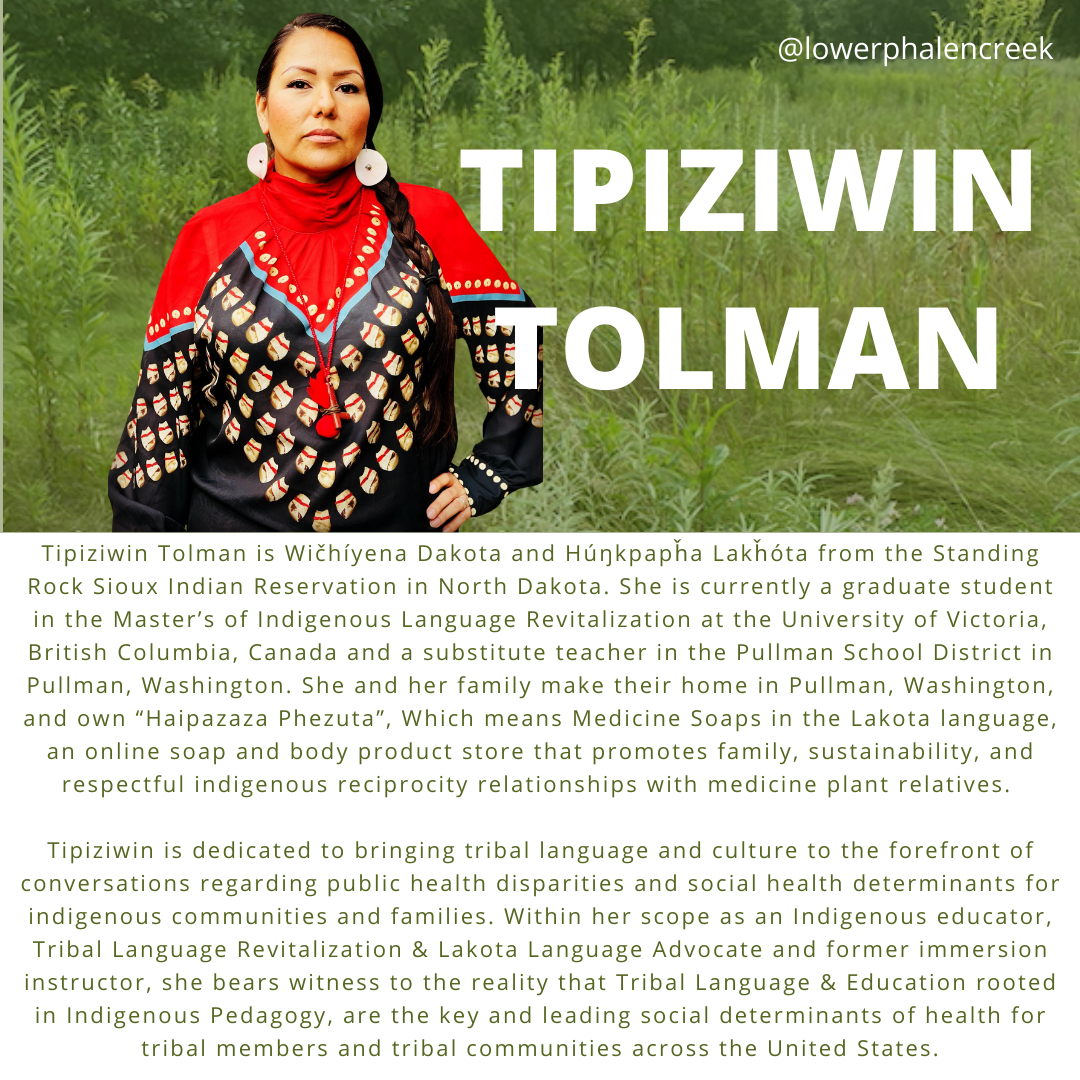

Photo taken by park-goer Kathy Sidles the morning before the diesel spill.

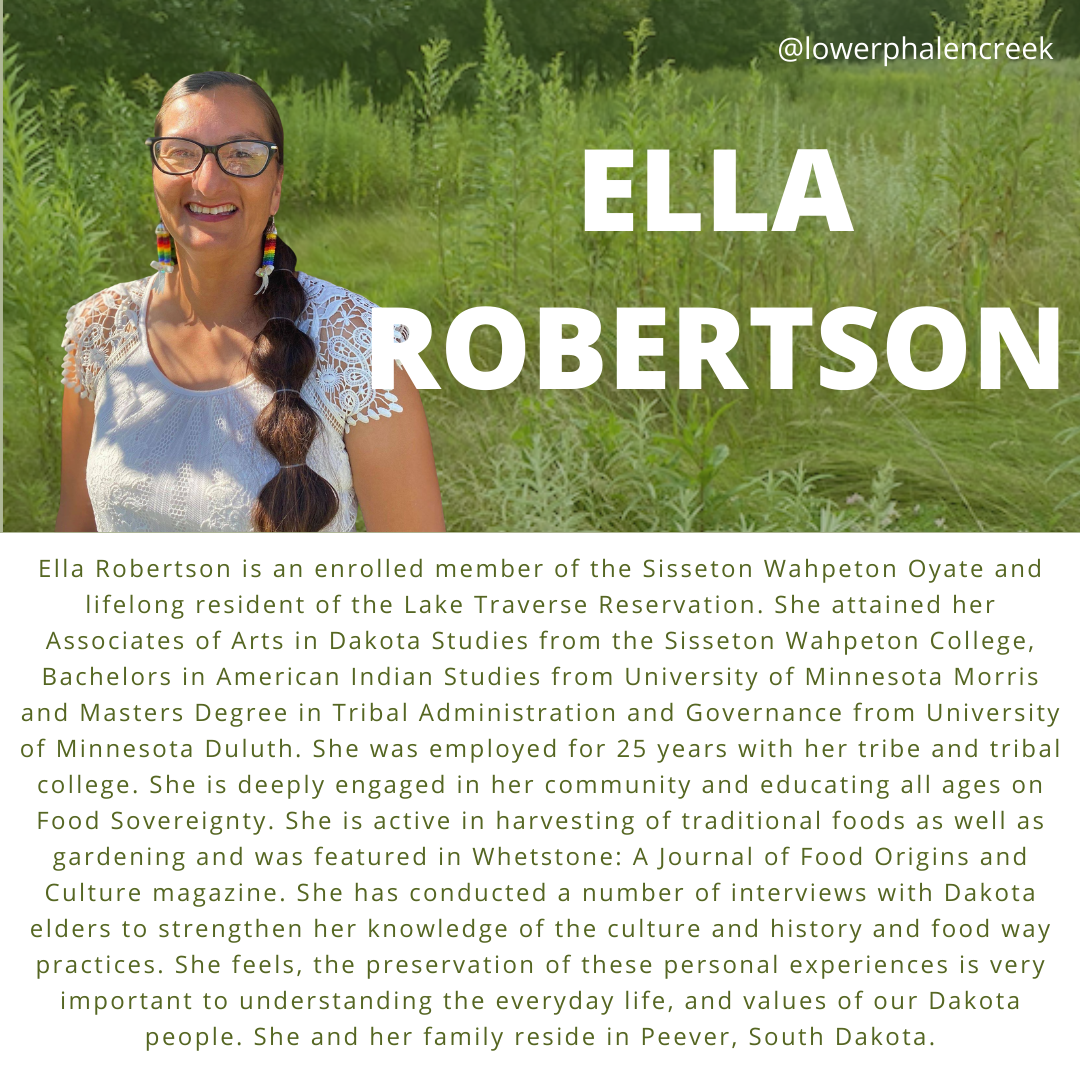

Multiple oil booms were placed along Battle Creek by Hazmat crews the week of the spill.

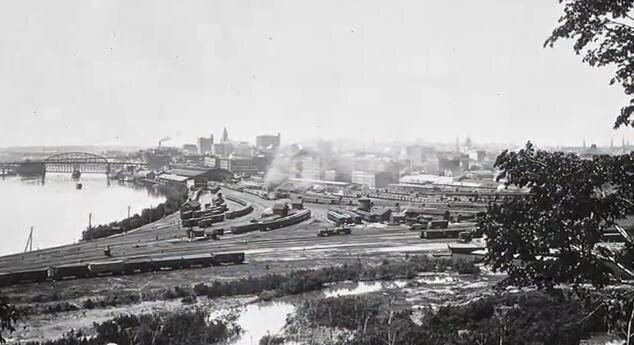

The 1,200-acre public park land in St. Paul known as Pig’s Eye Regional Park is the greenspace that too few people know about but whose story is much the same as Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary/Wakáŋ Tipi. The park is surrounded by private industry on all sides; to the west a wood chipper and soil dump, to the north and east the railroads, and to the south a scrap metal processing facility and asphalt plant, all of which present both a physical and psychological barrier to access the space. Historically, the site also earned the title of the state's largest unpermitted dump, accepting trash from nearby private businesses, industry, and the public for over a decade starting in 1956. To make matters worse, this dump site was put on a crucial floodplain area where waters travel to reach the Mississippi. Although it earned a Superfund site designation in the 90s with cleanup efforts starting in 1999, the site has been all but forgotten. For far too long this land has remained nothing short of a sacrifice zone.

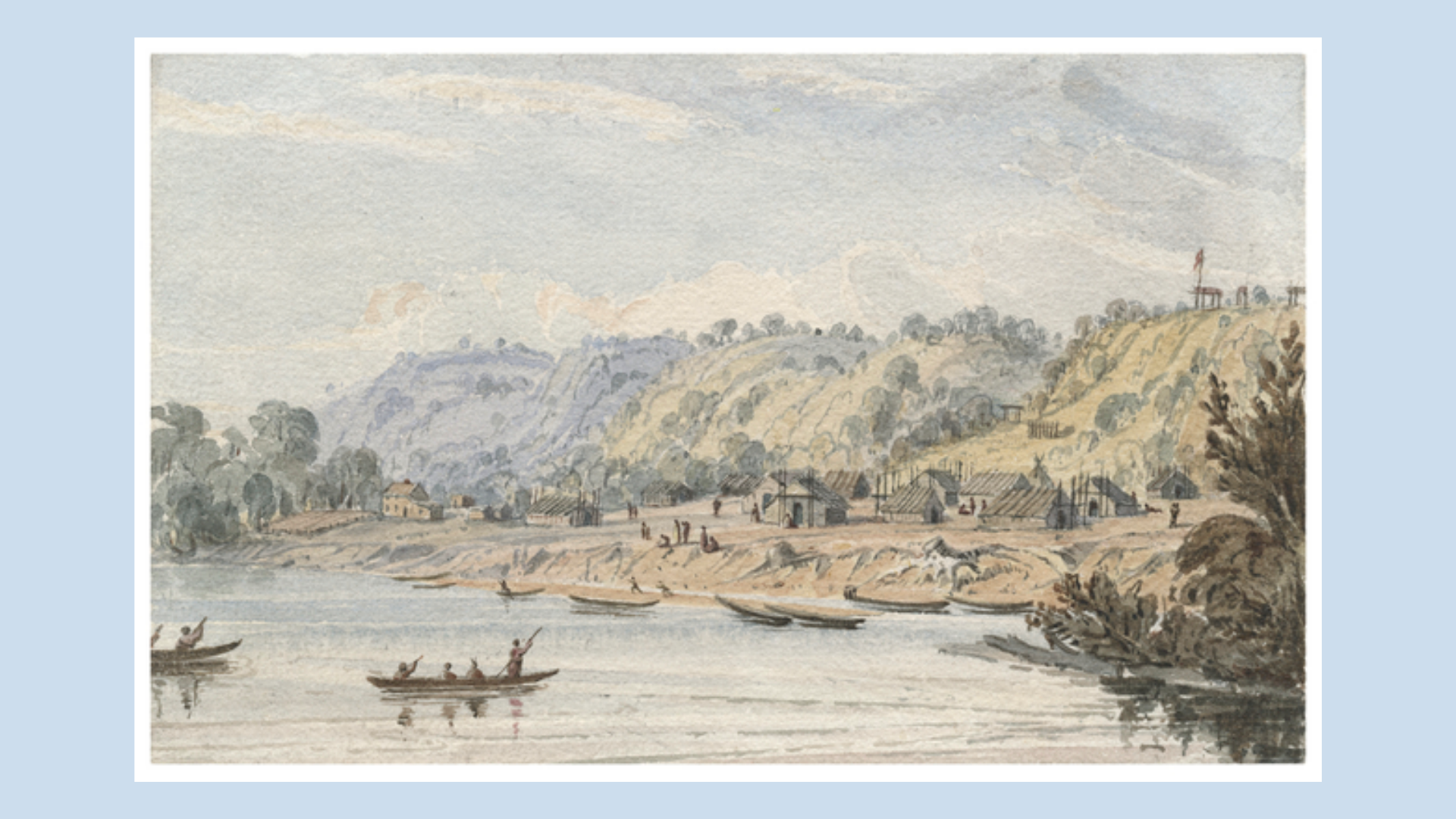

Even amidst these heavy industries and historical pollution, mother nature has staked her claim in the park. Clean soil and new trees planted in the area as part of the initial remediation have allowed winged and four legged relatives like the Great Blue Heron, the red fox, and eagles to return to the area known as Čhokáŋ Taŋka (the “big middle”) by our Dakota ancestors. Less than a mile from Wakáŋ Tipi Cave, it is easy to imagine the village at Kaposia using this land to hunt, fish, and gather in times past as Pig’s Eye Lake was once an area of great beauty, original to the landscape even before the Mississippi River was forced to remain in her current path.

But isolated within an industrial corridor, the burgeoning wildlife currently within Pig’s Eye Regional Park now faces threats of pollution from every side. The most omnipresent force being the railroad; the noise emanating from the railway reaching an eerie pitch every so often. The recent diesel spill that spread into the waters of Battle Creek which feeds directly into Pig’s Eye Lake is nothing new for the railroad industry in this area. In January of 2019, the Star Tribune reported on a 2,000-gallon diesel spill into Battle Creek, with the cold temperatures making cleanup more difficult as the fuel was trapped under ice. Another 3,200-gallon spill in 2018 went directly into the Mississippi after a Union Pacific train derailed at the Hoffman Bridge in St. Paul. Although diesel can evaporate making it shorter lived in the environment than crude oil, it is more acutely toxic to any plant or animal it encounters.

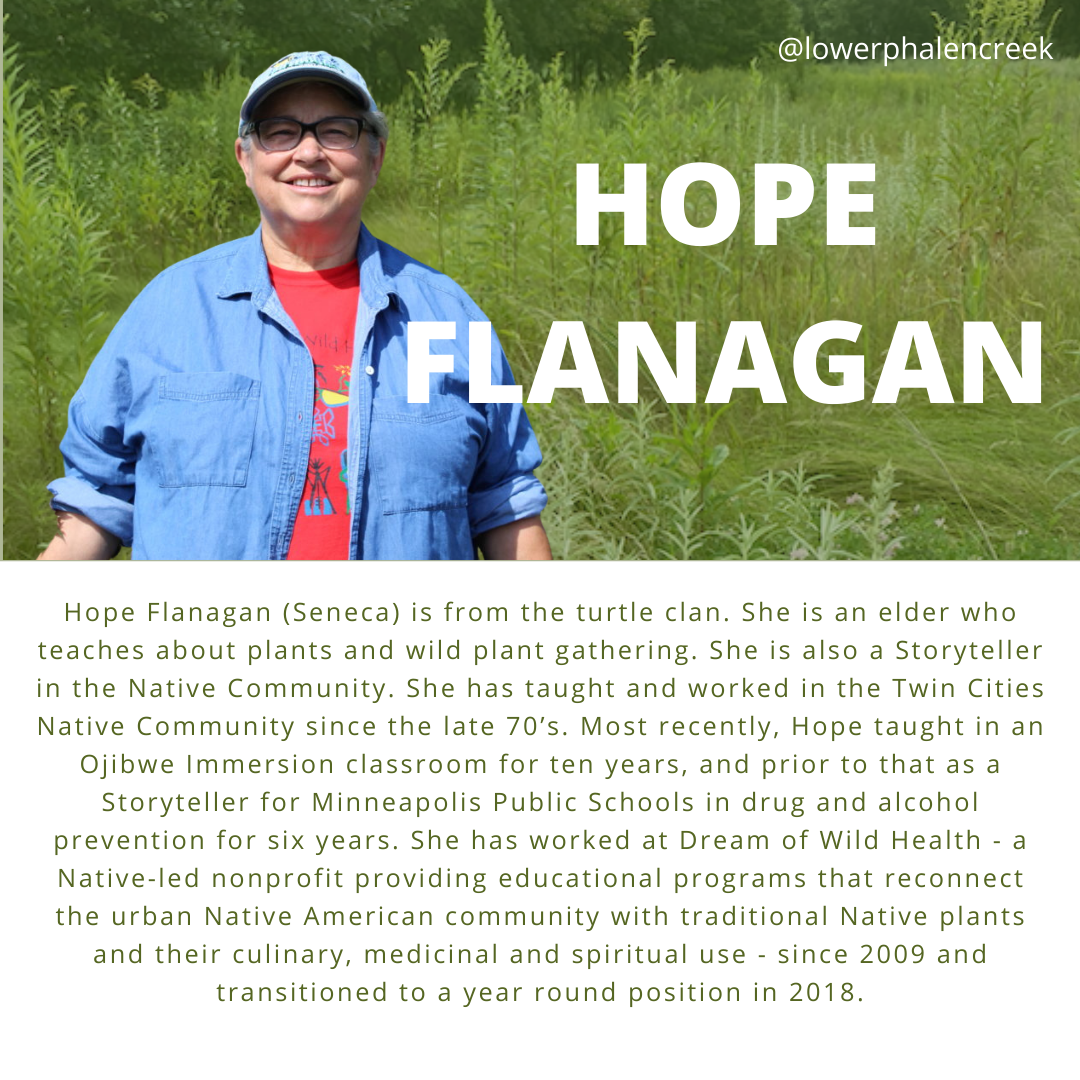

Photo of Pig’s Eye Regional Park with the adjacent railway to the East.

Of course, the larger the spill the more attention the press and the public may give it. But what about spills under 1,000 gallons such as the one last week? Were it not for the presence of community activists like Tom Dimond and Kiki Sonnen (artist who created the watercolor map featured above) to witness the presence of Hazmat crews days after the spill, the City of St. Paul may not have been alerted. The St. Paul Fire Department has its own emergency response team to contribute valuable resources and expertise, but the privately contracted cleanup crews arrived and acted without their input or support. Minnesota law only requires railroad companies to report incidents to the MPCA and not to the city.

To make matters worse, monitoring spills from the railroad through the MPCA database is difficult. While there are dozens if not hundreds of reports made each day throughout Minnesota, spill incidents can only be searched for by who reported it rather than by location. Hundreds of trains pass through the railway system in the area, making potential spills a key concern for the park; but the current tracking system makes it difficult to see any data for spills near and at Pig’s Eye Regional Park or to know the frequency of spill events, as even the smallest spills will have an impact if the trend continues over time.

Questions remain for how to hold railroad companies responsible for the spills they create. Beyond the initial clean-up efforts, will there be fines? And should private polluting industries contribute to habitat restoration if their presence is so heavily felt within the park? Government officials could start by demanding transparency about spills and prompt reporting to government agencies including the city, as this case demonstrates how easily pollution incidents can be swept under the rug. This is especially important in Pig’s Eye Regional Park as the city of St. Paul hopes to increase much needed access to the park and create more recreational opportunities according to their Great River Passage Master Plan. Although the surrounding predominantly BIPOC community in the Battle Creek-Highwood neighborhood could use the greenspace, these communities do not deserve a park that continues to be polluted.

If you are interested in visiting this beautiful park, email neighborhood activists Tom Dimond(tdimond@q.com) and Kiki Sonnen(kikisonnen@gmail.com) who give community tours and visit the park every week on Tuesday and Saturday mornings.

You can also show support for this park and express your concern over railroad pollution by emailing the local city council (ward7@ci.stpaul.mn.us) represented by Jane Prince, the district council represented by Betsy Mowry Voss (Betsy@southeastside.org) and Minnesota House Representative Jay Xiong (rep.jay.xiong@house.mn) who represents the district 67B containing Pig’s Eye.

Sample email format:

RE: Pig’s Eye Regional Park Pollution

“Dear (Councilmember/Representative) _____, My name is _____ and I am a (city) community member. The recent and ongoing pollution at Pig’s Eye Regional Park is distressing. I am writing to urge our elected officials to hold polluting industries like the railroad accountable for their actions. This includes timely reporting to the city as well as state agencies to allow for greater visibility. The surrounding communities and ecosystem deserve a clean and safe park space.”

![[Above, an infographic displays the gradually expanding criteria of eligibility for Minnesota residents waiting to receive a COVID-19 vaccine.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64246a1951853227e9ab9a0a/1680108105126-1PTS9QQ97AOZSWY3O8NB/MN+Vaccine+Timeline.png)

![[Our medicine bundles from this past spring included cedar, sage, sweetgrass, hand-crafted herbal lotions, immuno-support lozenges, and beautiful tote bags hand-sewn by members of our community.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64246a1951853227e9ab9a0a/1680108105130-RGP0BKL5W2KAZFYX78MY/IMG_3064.JPG)

![[Hillary Kempenich designed this public health campaign poster in November 2020 with the American Indian Community Housing Organization .]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64246a1951853227e9ab9a0a/1680108105134-KGWCEFXEBK5JMCY3XEDR/Masks+Up+Poster.png)